Until this turned up while I was looking for something else, I’d forgotten about the whole thing. It was a shock to rediscover that these words exist, and exist where anyone can read them. In 2008, in the fall of my senior year, I was invited to write a column for the student paper. It was a brief tenure. I called the series “small potatoes.”

The Chinese Quarter

In thinking about and researching notions of land, property, civility, belonging, I was captivated by newspaper accounts of Chinese in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America. The Chinese Quarter is a very short piece of historical fiction I wrote for the Cambridge University Social Anthropology Society Magazine’s Lent 2025 edition, themed “Fiction/s.”

Princeton Reunions

Princeton Reunions

One night, in the middle of the road in the dark

I stopped the car because I wanted to listen to the night sky

You sat next to me, and I’m sure you were anxious, and wanted to get home

But I opened the door, mutinously, as if you owed me this. Your enchantments, your promises

I heard nothing but silence, brittle and empty, although both of us wore smiles

One night, at the window, you made love to me in the dark

Fireworks splashed over the Princeton field, and your fingers over mine were silver, were gold

Afraid of the thunder and the flashing lights, your pup hid behind the washing machine

We looked for her, like before, padding all over in our bare feet. “Baby bear, brave bear!” Our voices ringing through your house

Once, after a walk along the old canal, you said she looked all over for me

You said you’d love me always. I bent over the page and sniffed the blue ink, to trace your loose hand

In the thick nights of summer I wrote to you, my face turned up at the sliver of moon. It glinted off the chimneys and was bright, so bright

I flicked the ashes of my cigarette over the roof and thought of you, sitting in the cool of your office while the day burned

I wrote to you by the panes of the coffeeshop, white-hot glass in the glare of the sun. You’d woken in the night and asked for me

I smiled at my reflection in your words on the screen. I thought of you, thinking of me

I’d parked the car so expertly on East Ninth Street

On the steps I cried and cried and cried, stoop-sitting with you in my city, by my park

People stepped around our feet and my tears, your blank face, your doll’s stare

My forgiveness – did you think it was funny then?

I looked into your eyes and I loved you, I loved you, I loved you

When you cried I held you, your head tucked beneath my chin, your shoulders shaking in my arms

“I’m so cold,” you said, your voice so small. I gave you all of my warmth

If I could take all of the bad things from you, take them away and carry them for you, I would, I tried

But you never thought of me, did you?

You owed me nothing. I deserved less.

“Morning,” you wrote, all the way from Sweden, and tacked on a photo of a subway ad

G A N T, it said.

And that was all, then. I’m your biggest mistake, your one regret

You asked me, “What am I going to do with all my love?” I believed you, I believed you

The rain beat against the windshield and I worried the tissues in my hands. They fell in pieces in my lap

I’d tell you, Just chuck it, like you did mine

But you never had any to begin with, did you?

Make me the monster, if it helps you. Lie, if it frees you. I don’t hate you

During Reunions I came giggling into your office with a pilfered pirate’s chest

You know I like boxes and, please, if it’s still there, I’d like to have it back

“Over and over and over again:” ice skating in New Jersey and around the world

This post is the final project for the course “Visible Evidence: Documentary Film and Data Visualization,” in the Department of Anthropology at Princeton University, Spring 2019. WordPress does not allow embedding of data visualizations, unfortunately, so I have included web links to the charts, instead. If you have a Princeton NetID, you may visit the original post, complete with all the pretty pictures (!!), here: Wei Gan Project.

[The documentary clips I present in this project are parts of a single film. When viewed sequentially and all together, these ten parts tell a slightly different story for a different audience from their incarnation here. The video in its entirety has a different feel and a different purpose, and these differences highlight interesting questions about data, sense-making, re-presentation, and narrative and its excesses and exuberances. Music accompanying each clip are either in situ or has, at one time or another, served as the real-life soundtrack to sessions on the ice. In making the film, I felt as if I was going back in time, or time was circling back on itself. I found myself wanting to create a kind of sensorium that evokes remembered moments and makes it possible to re-live them. The film, in full, tells at least three stories: my interlocutors’, the rinks’, and mine: what we saw, what we felt, and what we wanted to remember. Ultimately, however, I wonder if the final product is nevertheless my own self-reflection. If possible, I will ask my interlocutors to take the camera. I shared all or parts of the video with some of them, but the making of it was not a fully collaborative process. You can view the film in full here.]

“This Way and That Way” [1/10]

I first met Ira in the winter of 2018, a little over a year ago, when I picked up my ice skates after a ten-year hiatus and walked into the Hobey Baker Memorial Rink. Princeton – being Princeton – had its very own rink, a beautiful structure with enormous windows that opened up to the morning sun. It had a nice, four-days-a-week skating schedule, with the rink nearly always empty, a clean expanse of ice on which anxieties might suddenly be forgotten, sloughed away by the cold air like layers of old skin. I had a late start as a figure skater (eighteen, as opposed to, say, three), but it was something I had loved dearly, from afar, since I was a little girl. About a week after my (triumphant!) return to the ice, my ancient, cheaply made recreational skates broke, and on a whim I decided to go all out and acquire a professional pair heat-molded to my feet.

Usually a private skater who keeps to myself, I began chatting with Ira each time I skated at Baker. Looking back, I wonder if there is something efflorescent about an affective commitment to a hobby that opens one up to otherwise foreclosed social relationships. At least it seems so, for me. But Ira was easy to talk to, a friendly man who glided up and spoke to everyone. He was “sixty-six-and-a-half” when I first met him. He seemed to know all about the Baker schedule. He knew Seth, our zamboni driver. His was the music that played out of the speakers in the eaves. I learned that he skates six days a week, alternating between Baker and several other rinks near Princeton, and that Baker would close for the season far too soon for my liking. I had just started skating again! I have new skates! I don’t want to and can’t stop skating now! What would I do with no ice and no way to get to ice elsewhere? And so Ira offered me a seat in his car.

Ira and his car gave me the chance to get to know most of the available rinks in the area. Ira also knew everyone everywhere, and he introduced me to this person and that as the girl who “also skates at Baker.” Through him, I began to glimpse something more than just random people showing up to random rinks whenever there was public ice time. There was something of a network of spaces – Baker, Protec, Proskate, Igloo, Bridgewater – and something of an association of skaters that linked people, places, and temporalities together. When I began this semester’s project, I thought to build my ethnography around Ira as my main interlocutor and the lens through which to portray this skating “scene.” But, as another interlocutor would say to me much, much later, “You found a whole community, didn’t you?”

The first part of the video below follows Ira as he arrives at Protec. I chose this rink because it was the first one to which Ira took me, after Baker closed. The location is not important, however; rather, it is the arrival itself and the acknowledgment of folks who knew him. The video also signifies my own arrival – my introduction, and my visibility – to the adult figure skating “scene.” The montage sequence, first based at Protec and then moving on to Igloo, includes shots of me with other skaters. I wanted to show the movement of my own discovery of this “whole community” as it paralleled Ira’s years ago. What did I see? And what does it feel like for the anthropologist to be seen by her interlocutors, in return?

The second part of the video is an idiosyncratic summary of the rinks at which many of us (my interlocutors, including Ira, and I) alternately gather to skate. I will discuss the significance of ice, rather than rink – further on in the post below.

“Other People, Other Rinks” [2/10]

The material I gathered for this project reflects my gradual shift in focus, from a single person to a local setting to the international field of elite competitive skaters. After following the World Championships this year, I became interested in the careers of the skaters I watched perform. The International Skating Union, the governing body of the sport, changed its scoring system in the early 2000s and implemented it worldwide in 2004. The purpose was to minimize judicial bias and to standardize evaluation criteria, honing in on the execution of each specific element (e.g., “change foot flying sit spin,” “choreo sequence 1”) instead of sweeping “technical” and “artistic” scores based on a six-point scale.

The following are charts depicting the scores of up to the top ten placements in every ISU international Senior-level competition from the 2004/2005 through the 2017/2018 season (a total of fourteen seasons). These include scores from four Winter Olympic Games. I omitted the most recent season, just concluded, because ISU adjusted its scoring once more this past year. Charts are organized by discipline: Men, Ladies, and Pairs. (I have also omitted Ice Dancing because its elements are dissimilar to the other three disciplines.)

Each chart shows the overall score (top line) and its breakdown into the short program and free skate scores. [WordPress does not allow embedding of data visualizations, unfortunately.]

Some observers contend that the ISU Judging System encourages higher athleticism (e.g., increasing quantities of higher revolution jumps) at the expense of artistry. The level of skill exhibited by Tara Lipinski, who remains the youngest Olympic gold medalist (age 15 and 255 days, Nagano 1998 – the skater and event that introduced me to figure skating), would not go very far even in national competitions today. For the Men’s competitive field, especially, quadruple jumps have become almost required elements in the last few years, with those who can land only three-revolution jumps slowly falling by the wayside. In addition to the extra turn in the air, skaters are also embellishing their jumps with different take-off, mid-air, and landing positions to increase the level of difficulty – and thus augment their scores.

Below, during the 2017/2018 season, one of the youngest competitors in the senior men’s field, Vincent Zhou – age 17 – lands the first-ever quad lutz jump in any Olympic Games. This is a quadruple-lutz-triple-toe-loop combination, the most difficult jump combination (00:30):

[via @rani]

Vincent debuted as a senior skater in international competition in the 2017/2018 season and placed sixth at the 2018 Olympics. His highest scores, from the 2018/2019 season, fall outside of the ISU scoring cutoff of my database. Still, I wonder, do age, career progress, and familiarity with the (once new) ISU Judging System correlate with competition scores? It is difficult to statistically control for the increased athleticism, especially due to the entry of younger competitors; clearer patterns might emerge with scores over the next few seasons.

The charts below depict the performance of athletes who placed in the top ten in international competitions in Men, Ladies, and Pairs. I tried to demonstrate some relationship (or not) between the number of years with top-ten placement, the total number of events competed, and the percentage of those events in which a skater medalled (gold, silver, or bronze). Do older skaters have longer careers because they kept medalling? Or do skaters medal more frequently with more experience? How do younger skaters who have been doing quad jumps for years, just entering the field, stack up against older skaters? Please hover over each circle for additional information, including each athlete’s average number of events competed per year.

I then pulled the top ten overall scores achieved in each discipline over the fourteen seasons and tracked the careers of the competitors who performed those programs. Again, these charts include only the scores that earned up to tenth place. The first set of charts shows season’s best scores as a comparative measure of career highlights, while the second set of charts plots the skaters’ scores at each competition. The latter illustrates the ups and downs of individual competitors and the seasonal gaps in between. The second set also includes data on the top ten scores as well as the ages of competitors. These charts, along with the “Performance” charts above, reveal the state of the field in each discipline. For instance, the highest scores in Ladies appear much more recently, by skaters who have just begun their careers. The top male skaters seem to enjoy more sustained careers.

Season’s Best – Pairs

Career Scores of Top Competitors – Men

Career Scores of Top Competitors – Ladies

Career Scores of Top Competitors – Pairs

[Pairs skaters often begin as singles competitors. They also sometimes change partners mid-career, which accounts for the ages of the competitors above. Each skater of the three older duos had previous partners with whom he/she competed internationally. Pairs skaters do also end up as couples; Tatiana and Maxim are married…]

Some technical elements, particularly jumps, are more achievable biophysically for the male phenotype, which accounts for the gap in scores between Men and Ladies. The charts above also show how the increased athleticism effected the greatest impact on Men’s figure skating, while the other two disciplines are seeing much subtler upward trends in scores. The first quadruple jump ever landed in international competition was completed by Kurt Browning in 1988. Today, Nathan Chen, age 20, is christened the “Quad King,” landing as many as six quad jumps per program. For Ladies, by comparison, the first quad jump landed internationally by a Senior athlete wasn’t until this past season, in March, 2019 (although Juniors have been attempting them for years – with only two ever landed in international competition).

In recent years, however, young girls have begun training earlier and earlier for difficult elements (resulting in debates regarding their wellbeing). One such skater is a young lady named Isabeau, age 12, who trains at Igloo in Mount Laurel, one of my local rinks. She is coached by Yulia, and both appear in the clip “Technique.” On one occasion, Yulia proudly showed off one of Isabeau’s training videos on her phone to a group of adult skaters, including me. She told us that Isabeau will begin training quads very soon, well ahead of her fellow American skaters, because only about one percent of girls in the United States are doing quads while ninety percent of Russian girls younger than Isabeau are already landing them consistently. Eteri Tutberidze, one of the most preeminent Russian coaches, described the work of her students as “moving the limits” of female figure skating.

Here is one of Tutberidze’s students, Alexandra Trusova, age 13, landing a quad lutz in practice. Tutberidze also coaches Alina Zagitova, 15 when she won the 2018 Olympics (and one of the top female athletes in the charts above) – who, unfortunately (or fortunately?), is not doing quads…

Here is Elizabet Tursynbaeva of Kazakhstan, age 19, landing a quad salchow at the 2019 World Championships (00:50). Although this performance is not included in my database, this jump was the first-ever quad landed by a Senior lady in international competition:

[via @BossT Channel]

For comparison, here is Carolina Kostner of Italy, who debuted at the senior international level in 2002. Below is her short program at the 2018 Olympics, in which she placed fifth. She was 31:

[via @Buta Orjonikidze]

There are obvious differences in technical proficiency, but what of artistry? Has figure skating lost some of its beauty with the relentless push to jump higher and faster, to do fancier and flashier things?

For Men, here is Vincent Zhou again, at the 2019 Four Continents Championships. 2018/2019 was his second season as a Senior competitor, but just one year made a significant difference in both his technical skill and artistic presentation (compared to his Olympic performance, above):

[via @Brau Avitia 3]

Here is Javier Fernandez, another one of the top athletes from the charts above, performing a quad-toe combination at the 2018 Olympics (00:45). He was 26, just shy of 27, a decade older than his competitor Vincent Zhou (Javier placed third while Vincent placed sixth). Javier retired during the 2018/2019 season, after ten years on the senior international competitive circuit.

[via @Olympic]

Finally, here are Sui Wenjing and Han Cong, a top pairs duo from my charts above, at the 2017 World Championships, at which they won the gold medal. They perform a quad twist (00:40) and a throw triple salchow (02:35):

[via @мой канал]

Back at Igloo in Mount Laurel, Isabeau’s coach, Yulia, whom I mentioned above, is also working with a little girl named Valerie, age four. Under Yulia’s tutelage (if Isabeau’s accomplishments are any indication), Valerie is well positioned to join the ranks of the next generation of top Ladies figure skaters (representing what country, though?). Her mother accompanies her to the rink every day and sometimes joins her daughter on the ice, letting the four-year-old coach her. Below is a video of Valerie practicing her program, which she performed at a local competition in May. She runs through the routine at least once during each rink session, and the clips here are pulled from three separate iterations of her dress rehearsals – hence the beautiful blue dress. Off screen, Yulia can be heard giving instructions in Russian as Valerie goes along:

“Valerie” [3/10]

Despite the inherently competitive nature of figure skating as a sport, there is friendship and camaraderie between national teammates as well as international competitors. Many elite skaters join the casts of Stars on Ice, one of several professional shows, after each season. Fierce rivalries are transmogrified into off-season goofiness (see the Stars on Ice Instagram account). Nation-states and patriotism are big factors in the sport, but an in-depth analysis is beyond the purpose of this project. It is interesting just to note that athletes native to one country sometimes skate for another, obtaining residency or even citizenship along the way. Skaters also train outside of their own countries for various reasons, but most often to work with particular coaches. There are also only so many elite choreographers in the entire sport, so rivals sometimes not only train at the same rink but also skate programs crafted by the same people. The map below shows the training locations of each of the twelve top competitors (from the charts above) and includes information about support personnel and hours spent in training. Please click on the pins for the Infowindows; flags refer to the country that the athlete represents, and pin size reflects the highest score achieved.

https://weigone.carto.com/builder/1d0fa899-028e-4b56-a1e8-40884bd29e8a/embed

[The pins were originally dropped on the exact location of the training facilities (when the information was available), but some of the athletes train together at the same place, so overlapping pins obscured those underneath. In order to make visible all twelve competitors at once, I rearranged the pins; those clustered around the same city, therefore, are not accurate visual representations of location. Icons are made by Freepik, from www.flaticon.com, and licensed by CC 3.0 BY.]

Brian Orser and Tracy Wilson are two renowned coaches at the Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club, and, aside from the three listed on the map (Evgenia Medvedeva, Yuzuru Hanyu, and Javier Fernandez), they have worked with many other current international-level skaters. Prominent coaches also travel around the world to host skating seminars; Brian was just recently in China and ran a workshop on edge work with the national team. In April of this year, Vincent Zhou’s coach, Christy Krall, visited Protec in Somerset, one of my local rinks, for such a seminar, and I was fortunate to take part:

[Christy utilized the software program Dartfish (discussed briefly below) to help with analyzing jump techniques. Her tech setup is visible to the left of the frame.]

Georgian ice dancer, Otar Japaridze, in preparation for the Olympics, moved to New Jersey ten years ago to work with elite coach Evgeni Platov, a two-time Olympic gold medalist. He trained up to thirty hours a week at Proskate in Monmouth Junction, another one of the local rinks I frequent. His partner, Allison Reed, is an American who received a Georgian passport, and the duo competed for Georgia at the 2010 Winter Olympics (Allison’s siblings skated for Japan). Otar then teamed up with Angelina Telegina and trained full-time at Igloo, in Mount Laurel. Igloo’s skating director is a former two-time U.S. Pairs national champion and tenth-place Olympian, and he runs an elite international training program at the rink. Several other Olympians also trained here and subsequently stayed on as coaches (e.g., Nick Buckland). Otar and Angelina competed throughout the 2013/2014 season but did not qualify for the 2014 Olympics. After retirement, they married each other and “made a home” in Mount Laurel (as one of my interlocutors explained), and both currently coach at Igloo. Below is Otar and Angelina’s free skate from the 2013 Ukrainian Open:

“Otar and Angelina” [4/10]

[Not long ago (perhaps inspired by viewing a rough cut of my film), Ira played the tango from this performance at the beginning of his lesson with Otar, while Angelina was also on the ice working with Valerie. Both immediately recognized and reacted to the music, which prompted a few laughs from the rest of us.]

I first learned of Otar last spring, when Ira listed all the coaches worth enlisting in the area. He was still working with Andrea at Protec at the time, but two other interlocutors, Judy and Elizabeth, were skating with Otar, and I heard all about it via Ira. While I was away in the field last summer, Ira switched to Otar as his coach (“abandoning” Protec) and began skating regularly at Igloo for this reason. As Ira is still my ride to the rink, I began to skate at Igloo, too, which then became the main site of my documentary project.

“Now that I work with Otar” [5/10]

As any aspiring figure skater would attest, fancy things are cool and everybody wants to do them. Just recently, one of my interlocutors, Jane, an adult skater and Yulia’s student, asked me about her broken leg sit-spin. She said, “I want to do something fancy! I want Yulia to teach me something fancy!” Me, too, I echoed. When I first started skating, I was fortunate to find two very good coaches at a rink in North Carolina, and they helped me move through each of the jumps and spins in turn. I felt fancy! And I eschewed all exercises like a musician might avoid doing arpeggios. Upon my return to the ice, however – and, perhaps, with age – I finally understood that there are basic things about balance and body posture that I was too impatient to work on and so generally dismissed. I began working with Otar, too, a few weeks ago, after Ira helped set up a lesson for me. After my first lesson, during which we did exceedingly basic things like stroking and crossovers, Otar commented, These skills will help you with everything, but no one wants to do these exercises; everybody wants to do the fancy stuff – “Because they’re boring!” I exclaimed.

In figure skating, each competitive performance begins with a short program that lasts just under three minutes, followed by a free skate of four to four-and-a-half minutes – if the skater(s) qualifies. For eight minutes in the spotlight, as glamorous and effortless as they seem, skaters dedicate hours upon hours upon hours of preparation. It has taken me my entire adult life to understand that figure skating, like everything else, can only be built up bit by bit. The basic things add up to the fancy things, just as we read Durkheim in our proseminars before getting to the stuff about rocks.

Discussions about technique are frequent and necessary conversations among figure skaters. Skating is a sport that requires very precise execution of complex elements. By execution, I mean the perfect arrangement and timing of all body parts, in motion over time and across space: skaters have no more than 0.2 seconds to get their feet together in the right position when launching into a triple jump. That’s half the time it takes to blink (0.4 seconds). They jump two feet off the ice and land at about fifteen miles per hour, on a 3/16-inch-wide blade. In the air, they turn at 450 rpm, or seven revolutions per second, aloft for no more than 0.7 seconds. The force of landing can be up to eight times their body weight – on that 3/16-inch blade, at fifteen miles per hour.

Skaters video their elements, and elite athletes use software such as Dartfish to further analyze the footage to pinpoint exactly when, where, and what something needs to be adjusted. This inherent ocular reflexivity as well as the always already performative aspect of figure skating add interesting wrinkles to the politics of representation and ethnographic filmmaking. At the rink, my interlocutors sometimes film themselves, poring over the technique of a spin or a jump. Bill and Cindy reviewed footage of their ice dance routine with Otar to evaluate the execution of each element, and they linked the quality of their performance to its presentation for an audience (see “Bill and Cindy”). Ira, as he watched the rough cut of my film, couldn’t help but comment on own his skating (sometimes positive, sometimes negative) each time it appeared on camera. On and off the ice, my interlocutors also often consult each other about positions and movements, debating, demonstrating, attempting. Otar explained to me, You have to always be aware of what you’re doing. As a deeply cognitive yet literally corporeal work on the body, figure skating technique reflects the ways in which skaters self-consciously inhabit their physicality, their space, and, ultimately, their selves.

Vincent Zhou, somewhat notorious for under-rotating jumps, wrote the following on his Instagram page after a less-than-perfect performance at the U.S. Figure Skating Championships in 2018:

“I’m proud of myself for skating two great programs and giving people a little something to have faith in me for. I’m just trying my best to do what I love without the people who dislike me weighing me down. It’s just my first year being a Senior internationally, and I’ve improved by leaps and bounds over this rollercoaster of a season. What a great way to start 2018–with better performances, a number of quads that I know were clean, and an absolutely incredible audience. Thank you all so much for your belief in me–even when I sometimes struggle to believe in myself. I gave it everything I had, and there is nothing more I can ask of myself.”

A month later, Vincent placed sixth at the 2018 Olympics.

While the conversations in the clip that follow may seem esoterically technical and of interest to no one save their participants, the underlying lesson that I took away from them and their iterations is the value of process, waiting, and being-with. Talking in the car, for half an hour on average each way, Ira taught me to think of skating as a metaphor for life itself. He used to tell me about living life “on the edge,” a cheeky (but not really) reference to edge work on figure skates. The analogy is extendable and has become more complex as – cheekily – time passed and life went on. Just as a skater must slow down and hold the edge to wait out its curve, so a person might try to be patient and live in the present, being with and “holding” instead of rushing through, thrashing about, or running away:

“Technique” [6/10]

Otar travels to Proskate for his lessons with Judy and Elizabeth. Of the adult skaters at Igloo, Otar also coaches Jane, Cindy, Bill and Cindy as a dance duo, and Dawn, who skates mostly at Protec. Bill also works on ice dancing with Angelina. Yulia, who performed the salchow, the waltz, and the flip in the video above, also coaches Jane. Two little girls, Valerie and Carolyn, share the public rink with us during their lessons with Yulia (as opposed to the freestyle rink). Carolyn has two older sisters, though, who skate on the freestyle rink. I mention this because, while we work on the public rink, aspiring Olympians are simultaneously training on the freestyle rink, just on the other side of the mezzanine. Isabeau, also Yulia’s student (and the triple-jumper in the video above), has already been invited to join the U.S. team for the 2022 Winter Olympics.

One thing that struck me about figure skating in general and the Central Jersey “scene” in particular is the recursive and para-sitic nature of the sport. The rink itself is elliptical, with ends but neither beginning nor end. Elements flow smoothly into each other rather than terminate abruptly at every conclusion. Body parts are connected, still but always in motion. Skaters work on elements over and over and over, run through their programs again and again and again, at one rink or another, with different coaches, sometimes in different states or different countries, and temporalize accordingly. I took my skates with me to China during fieldwork last year, and I shared the ice with former and aspiring Chinese international competitors. The feeling was palimpsestic. It seems that clock time and geographic space are not identifiable, not important.

Ice is the main distinguishing characteristic of each rink, as Ira and I discussed in “Other People, Other Rinks,” above. But even then, “rink” isn’t quite the locus of difference, either. Ice – not time, not space – marks each rink, but it also marks each practice session. Ice is the same everywhere (it’s just frozen water) – but not. Ice is a central topic of conversation among all of my interlocutors. Typical pre-session comments include: How is the ice today? Are they going to cut it? Bill doesn’t care, but I can’t skate on that. They brought somebody else in – I’m not sure how he’ll do the ice (talking about an unfamiliar zamboni driver). And, once on the ice: Is the ice softer than usual? The ice is so nice! This ice is crap! I’m going to have a word with Joe! The first question Ira posed to me after I tried out the rink in China was: “How’s the ice?” When I talk to other interlocutors about visiting China, they also asked, Are there rinks there? How are the rinks in China? What is significant is not “China,” or “Protec” versus “Proskate” versus “Igloo;” it is the ice.

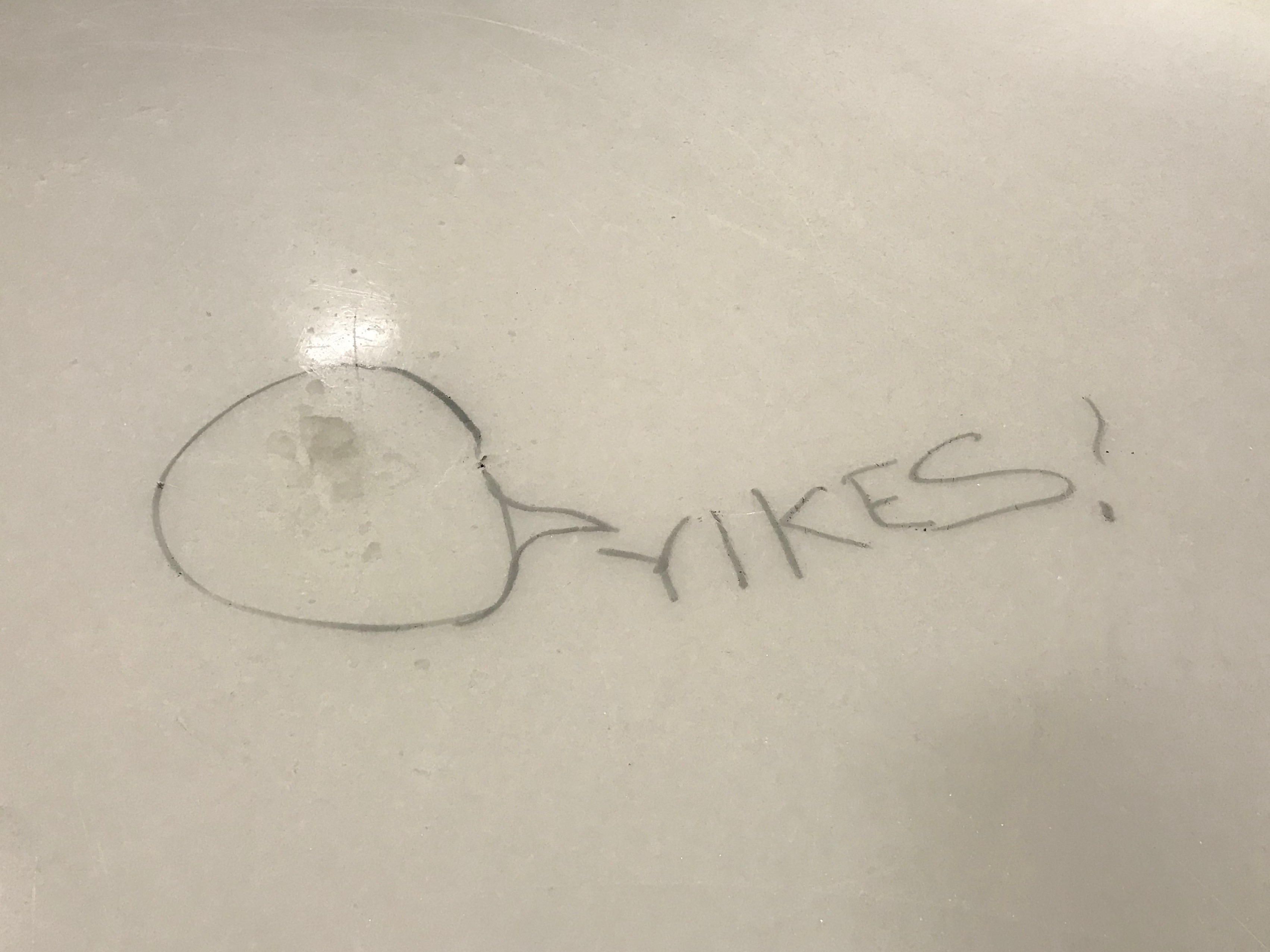

Ice is discursive, and affective, and, also, visual:

[Courtesy of Bill and his permanent marker]

There is something of an intensity of figure skating that reproduces itself, folding together disparate people, places, and times, grafting onto nothing more than the surface of the ice – as if ice alone is enough to structure spacetime. Ice time is perhaps, phenomenologically, icetime. My interlocutors contrasted rollerblading, rollerskating, and ice skating, and all agreed: ice is better. They have also described skating as a passion. Several interlocutors “play hooky” from their jobs and run off to the rink. “It was a part of who we were,” Cindy said about her program music; the same can be said of the sport itself.

“Therapy” [7/10]

The video clip below is a compilation of skating lessons. First, I wanted to cut together lessons that circle around the perimeter of the rink to demonstrate repetition for itself, both in moving across the ice and in the moves themselves. I also wanted to show the sense of presence that saturates the ice when it is filled with people and the spirit of their work-as-passion. Ice is social; it marks difference – and is differentiated in turn – socially. My interlocutors and I, at every rink, are used to (spoiled by?) clean surfaces, open patches, and few people. Whenever “the public” become more nuisance than noticeable, someone would always gripe. Once, while putting on our skates, we were all peering anxiously around the corner: I see people coming in! And: Sharon, why did you let all these people in? They told me a party will be coming in at noon. That’s the “pond skater” (a young man who cuts up the ice in his hockey skates). They’re putting the cones out! Who are these people??! One morning, I absentmindedly drove to Igloo instead of Protec and only realized halfway that that had not been a sensible choice. I told Bill and Cindy about it and, without waiting for me to finish, Bill said, “It’s the company.”

My interlocutors never skate alone – accompanied as they are, in this clip, by their coaches. But one might argue that no one ever skates alone; there are always others on the ice who know exactly what Ira means when he says, “you’re just sort of floating through space.” Even when there is only one body on the ice, there is still the ice itself, and one’s own gaze, and the shared potential of spectatorship.

“Lessons” [8/10]

[The two musical pieces accompanying this clip are “Willow Waltz” and “Ten Fox,” from U.S. Figure Skating’s official ice-dancing test music repertoire. Jane put them on each time she had a lesson with Otar – just these two – for weeks. She – or, rather, Otar – has been adding more variety as of late, due perhaps to recent squabbles over rink music.]

Figure skating, as a governed sport (institutionalized, or, as Deleuze would say, “massified”), evolves in linear time, with the ebb and flow of generations, in an arrangement of geopolitical space. The map below shows the number of medals earned by country and by discipline. The data here aggregates all of the fourteen seasons of my database. What might be some factors that contribute to particular countries’ dominance in one discipline or another? Please hover over the skate icons for the Infowindows; for the other layers, hover anywhere within a nation’s borders).

https://weigone.carto.com/builder/4acb1286-04ba-4f58-8c69-d0c35fcb9cdf/embed

The following map tracks the changes in medal distribution from the 2004/2005 to the 2017/2018 season. A darker orange denotes higher total medals earned.

[The accompanying track introduced each group of competitors at the 2019 World Figure Skating Championships.]

I conclude with Bill and Cindy, a 72/76-year-old couple who began skating about fifteen years ago, “after,” as the announcer of the Princeton Skating Club showcase described, “a full-time working life.” They first met Ira (and Judy) at the Protec Coffee Clutch (mentioned briefly in “Now that I work with Otar,” above), and it was Bill who informed Ira that Princeton has its own rink (Ira lives in Princeton). I first met Bill at Baker, and then I got to know him and Cindy better once I began skating at Igloo. Bill and Ira have been jokingly dubbed “the kings” of Igloo – but there are also “queens,” and the latter most certainly call the shots. One day, toward the end of my fieldwork, Bill and Cindy came to the rink all dressed up. I watched them run through an ice-dance routine with Otar and learned that they were to perform at an exhibition at Princeton Day School.

The first video below is of my interview with Bill and Cindy, and the second is of their conference with Otar, which I was fortunate to be able to film. For me, this conference captures the ethic of figure skating and embodies, most of all, the love and co-presences that render the sport a work of art.

“Bill and Cindy” [9/10]

“Conference” [10/10]

[My gratitude to everyone who put up with me and my iPhone. In order of appearance: Ira, Otar, Chris, Lin, Max, Marguerite, Andre, Gail, Minka, Sharon, Jane, Joe, Carolyn, Cindy, Bill, Inga, Kecy, Judy, Wendy, Yulia, Lucy, Penny, Valerie, and Angelina.]

Music:

Chandelier – Sia

You’re the One that I Want – John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John (Grease)

Just Can’t Get Enough – Depeche Mode

Happy – Pharrell Williams

愛のオルゴール Music Box Dancre – Kentaro Haneda

String Quartet No. 15 in A Minor, Op: 132: III. Molto Adagio – Beethoven, Tokyo String Quartet

Night Sky – Brian Crain

I’m Not the Only One – Sam Smith

Come Undone – Duran Duran

Exogenesis: Symphony Part 3 (Redemption) – Muse

A Shout Across Time – Ira Mowitz

Out of the Blue – Debbie Gibson

Ten Fox 3 – USFSA

Willow Waltz 2 – USFSA

C’mon C’mon – One Direction

A Thousand Years – Christina Perri

Sun (Instrumental) – Sleeping at Last

Spirit of Charity: The Moral Economy of Chinese Philanthrocapitalism

[This is a paper, based on preliminary fieldwork in China in the summer of 2018, given at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, in San Jose, California. The title is from my pre-field abstract submission, while the content reflects nuances gleaned from fieldwork.]

The World Giving Index is an annual report, now nine years running, that measures the level of generosity of countries around the world. This year, out of the 146 nations polled, China came in at 142. Chinese are not typically portrayed as a particularly charitable bunch, and these yearly polls, picked up by mainstream news outlets like The Guardianand The Washington Post, certainly add to this view. At a panel on Chinese and Chinese-American philanthropy in New York City earlier this year, the speakers, a group of distinguished Chinese-American philanthropists, began their discussion by extolling the Chinese “spirit of charity.” “The seed for charity is our DNA,” one of them announced into the microphone. This statement was met with some discomfort from the audience, a perceptible moment of uncertainty and confusion. I wondered, why is there a disconnect between doing philanthropy and being Chinese? Why the rush to smooth over it by invoking some innate, essential quality?

Initially, I set out to explore philanthropy as a rising phenomenon among Chinese and Chinese Americans. I wanted to follow the ways in which philanthropy is mapped onto tradition, entrepreneurship, geopolitics, and circuits of capital. I also wanted to dig deeper into the back stories of philanthropists themselves. While these concerns continue to be relevant, I realized, over the course of three months in the field this summer, that perhaps this wasn’t quite the story that needed to be told.

In Beijing, I attended a congress organized around one of the hottest topics of the day: the federal government had proposed an overhaul of the statutes that regulate the operation of civil organizations, which include charitable foundations, social service providers, nonprofits, and NGOs, and it was soliciting recommendations from the public before ratification. In response, meetings such as this one took place all over the country. Here, in the capital, the heads of more than forty organizations were in attendance, as well as Party representatives, scholars, and journalists. The organizer, a powerhouse of a woman who has been involved in this arena for more than two decades – I’ll call her T – described her feelings toward the shifting terrain of philanthropy in China: “I haven’t left this world since 1993. I’ve seen it all, and I’ve done it all. After we passed the China Charity Law two years ago, I harbored so much hope for the future of our work here. And now this is undoing all the progress we’ve been making. Why is it that everything else – our economy, our technology – has hurtled forward, and yet our ideas and our politics are still stuck in the same place?”

We were clustered around three large tables at the center of the room, and T’s comments sparked a flurry of rebuttals from every direction. I watched these impassioned exchanges in silent wonder. The Party representative fought to get a word in, and T immediately shot him down, and then someone else, a younger woman, cut T off in turn: “You’re taking up myfive minutes!” she hissed. The deputy secretary general of the China Charity Alliance sat rigidly in his seat, scowling. The room seemed to get hotter. Barbed critiques flew back and forth, but it was the emotional force animating their words that filled the room.

One of T’s remarks was especially poignant. “The philanthropy-charity sector is like the sea,” she said. “Here we are, with our authority and spheres of influence, and we think that we are the ones shaping the future. But we are nothing more than little islands floating on the surface, and it is the sand at the bottom of the sea – the small, the local, the ad hoc assemblies, the ones disavowed by the state, the ones ignored by us – that is churning and carrying us toward the issues that are truly important. We need to pay attention to and foster the power of society itself, the power of the sand and the sea.” (My translation doesn’t quite do her words justice.)

Philanthropy and charity as we understand it here in the United States – the Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, religion-based organizations, even the Red Cross – have no direct counterpart in China. Philanthropy is simply not translatable; it does not have a linguistic equivalent in Chinese, much less structural, discursive, or affective analogs. Chinese and Chinese-American practitioners employ the term 公益, or public interest, sometimes in conjunction with 慈善, or charity, to refer to their field of action. These terms, however, encompass a wide range of concepts, actors, practices, and organizational forms. “Philanthropy” is a construct that indexes a particular mode of capital exchange, intimately tied up with liberal notions of the individual, the social, and the norms of reciprocity. It is also a particular way of seeing and circumscribing social action and social relations. As such, “philanthropy” comes with a whole host of assumptions. It was uncomfortable to hear the speakers on the philanthropy panel in New York defending the Chinese spirit of charity precisely because philanthropy does notexist in China the same way it does in the U.S. At best, it is an awkward framework forced around complex and diffuse assemblages. It is telling that the only people concerned with putting a definitive name on this emerging field of practice are, well, the Americans. “What is the difference between 公益 and 慈善?” the executive of a U.S. nonprofit asked me. “Which is the proper term for philanthropy?” I posed this same question to many of my interlocutors in China, and their responses ranged from curiosity to indifference to exasperation. This is just what we do, they told me. We’re trying to improve the material conditions of life, broaden social consciousness, solve social problems, create social value… Why does it matter what you call it?

However, practitioners both in and outside of China recognize that there are significant operational issues when it comes to, for example, strategic investment, juridico-legal regulation, financial accountability, and social efficacy. In short, they realize that they don’t really know what they’re doing, only that something needs to be done. They look toward American models of philanthropy, invite European experts to train young philanthropists, borrow from Western philosophy and social science, apply methods and concepts they learned at Ivy League management schools, to understand what they’re trying to do. They try on ideas like clothing, testing, evaluating, making decisions at all levels of institutionalization to formulate the best way forward. As many of my interlocutors explained – wryly, self-deprecatingly, honestly – “We’re crossing the river by feeling for the stones under our feet.”

Toward the end of my fieldwork, I flew to Inner Mongolia for a three-day conference on cross-strait philanthropic collaboration. It was jointly sponsored by the China Charity Alliance, a state-affiliated organization, and the Lao Niu Foundation, a private charity worth more than half a billion dollars. Its founder is a retired entrepreneur who donated all of his profits to this charity, headquartered in his hometown – where, not coincidentally, the conference was held. On our second day, Lao Niu Foundation staff took all of us (some three hundred people stuffed into six coaches) on a tour of its local projects. One of these projects was a conservation effort, in partnership with The Nature Conservancy, that sprawled across a vast expanse of farmland gouged by rocky ravines like enormous claw marks. The project’s long-term goal is to restore the land for agricultural use so that local farmers can “lift themselves out of poverty” while learning about the importance of conservation. I know how that sounds, and I know how problematic the rhetoric – and even the project itself – is, but, at the day’s end, when I stepped off that bus, into the dusk, I couldn’t get the sheer physical scale of the project out of my mind. I felt inspired, energized, abuzz. The image of tiny little pine trees planted in – actually, swallowed up by – the jaws of mighty canyons eroded by sand, wind, and water – swam around in my head. I couldn’t get over the enthusiasm that I had heard in our tour guides’ voices, undercut with a quiet pride and sense of purpose.

Mostly, though, I was abuzz with the conversations that I had listened to on the bus, all day long, as we were ferried back and forth from place to place. Everyone around me – men, women, new initiates and old hands, from every corner of the country – spoke earnestly about the work each of their organizations was doing. There were endless questions about their respective strategies, obstacles, successes, and failures. They compared notes and lessons learned. They complained about the government. They discussed the moral underpinnings – or lack thereof – of philanthropy in China as a whole. They were obsessed. At one point, just before we returned to the hotel, I sat, exhausted, drinking coffee and in utter disbelief at how much intellectual debate was still going on all around me. It seemed so laborious, after such a long day, but it wasn’t; it was pleasure. I commented to K, a new friend I’d made, “How are they still talking about their work?” She laughed. “Well, what else would they be talking about?”

Off the bus, I wanted to share my exuberance, this affective energy, with someone. I sat on a bench as the sun set and began to tell a friend and colleague of mine about my experiences that day. He was immediately skeptical: “Interventions like these come in, wash over the town, recruit people, actually convert people into really believing in them, then wash away without results. Why are they there? Can they correct more fundamental distributions of power that keep locals in their place?” And so on.

I found myself rising to my interlocutors’ defense. It was an odd compulsion: strangers, they all were to me. I had only spoken with them intermittently, in awkward Chinese. Most of them, in fact, had initially regarded me with undisguised suspicion because I was unaffiliated with an organization – and I looked like a foreigner. But there was something that buzzed in the air, something of their conversations that lingered, something about having shared an enclosed space with other bodies for nearly ten hours, something about having seen, all of us together, the material – the very real – traces of someone else’s dream. I knew my friend was spot-on with his analysis. But I needed to defend my interlocutors. I felt deeply that there was something to defend. I didn’t quite know what that was, or how to defend it. But there was something there, something that pulled my interlocutors along, stumbling over the stones in the river, toward something, something that also pulled at me.

We all know of Durkheim’s “collective effervescence,” or the mimetic contagion of the crowd. But I think Mauss is appropriate here: “there is, above all,” he writes, “a mix of spiritual bonds between things that are in some way of the soul, and individuals, and groups who treat each other, to some degree, as things.”

I am suggesting, then, that we think of philanthropy in a slightly different way. Rather than instituting a series of dyadic relationships between donor and receiver, between gift and counter-gift – even if ultimately circular or interpenetrating – and wondering if we are looking at altruism or self-interest, we look instead at the generative potential of different sets of relationships across different registers and constellations. Rather than thinking through the equivalence of value in exchange and reciprocity, we think through value, as Nancy Munn tells us, as relative potencies that spill out beyond the strictures of any single transaction. Rather than beginning with the act of giving and the figure of the giver, we start with the ask, the demand of the social world for its own reproduction. As I mentioned previously, 公益, the makeshift label denoting philanthropy in China, translates into “public interest.” But, as the head of a prominent Beijing-based charity explained to me, 公益 is actually a contraction of a longer phrase: 公共利益, which signals “that which benefits the public.” In that light, what might philanthropy look like if we started at the membranes of social relations? Must we locate practices of giving in discrete entities like theindividual, the philanthropist,thecharity, and ground them in an origin myth of morality or religion or power or capital accumulation?

Something more, something in excess of capital and exchange and narrative structure, emerges out of disparate, often mundane and sometimes emotionally charged, actions. Crossing the river by feeling for the stones – but where are my interlocutors going, and why? No one seems to know, and the lack of an answer doesn’t seem to matter. They engage in concrete acts with material outcomes, sometimes in disagreement with each other, but it is as if each of them is working on a piece of a shared, larger puzzle that no one can quite see or name. By participating – by taking part in or being a part of – projects oriented toward and constituted by social relations, my interlocutors in turn constitute themselves as well as an unknowable yet sensible and potent whole. If the political is cracking open the visible from the inside, I think of this generative capacity, this energetic excess, this something more, as an emergent commons constantly being reinscribed by every act – by feeling for the stones. If the ends are unknown and the means are contested, then the logic of economy is no longer enough. Chinese and Chinese-American philanthropy becomes a political project, a process of taking the given – national and international politics, capital flows, Western and Party ideologies – and opening spaces within it to try on new clothes, to play, and to decide, in William Mazzarella’s words, “how we become what we can be in relation to each other.” Ethics and morality here is cartographic rather than archaeological. I think of T and how disappointed she was that “politics” in China seem intractable. Yet, this does not stop her nor her colleagues from being attuned to the social – to the sands and the sea – in an effort to reinstitute the political.

When I returned to the U.S., I attended another panel on Chinese and Chinese-American philanthropy, this time with slightly different eyes. One woman – a Chinese-American social entrepreneur with projects in both China and the U.S. – spoke about the complexities and shortcomings of philanthropy in China. It was interesting to me that, despite the depth of her discussion, the one issue that captivated the audience the most was the education and training of Chinese practitioners on how to do philanthropy. The conversation I had with my friend about the Lao Niu Foundation’s conservation project came to mind: philanthropy – what falls under its rubric, what it does, what it answers to – is different depending on how one chooses to see. Back from the field, I find myself struggling to hold in tension these different ways of seeing, and writing this is a reminder in itself that there are other questions to ask, and other stories to tell.